The Kid, the Scientists, and the Walk That Changed Everything

For most of his nine years, Theo Brewer couldn’t walk without falling or tripping due to an unbalanced gait. Then a team of researchers in UNO’s Clinical Gait Analysis Lab wired him up with sensors, watched how he moved, and gave his doctors something no one else could: answers.

- published: 2025/09/23

- contact: Sam Peshek - Office of Strategic Marketing and Communications

- email: unonews@unomaha.edu

In the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s (UNO) Biomechanics Research Building, the Clinical Gait Analysis Lab always starts quiet.

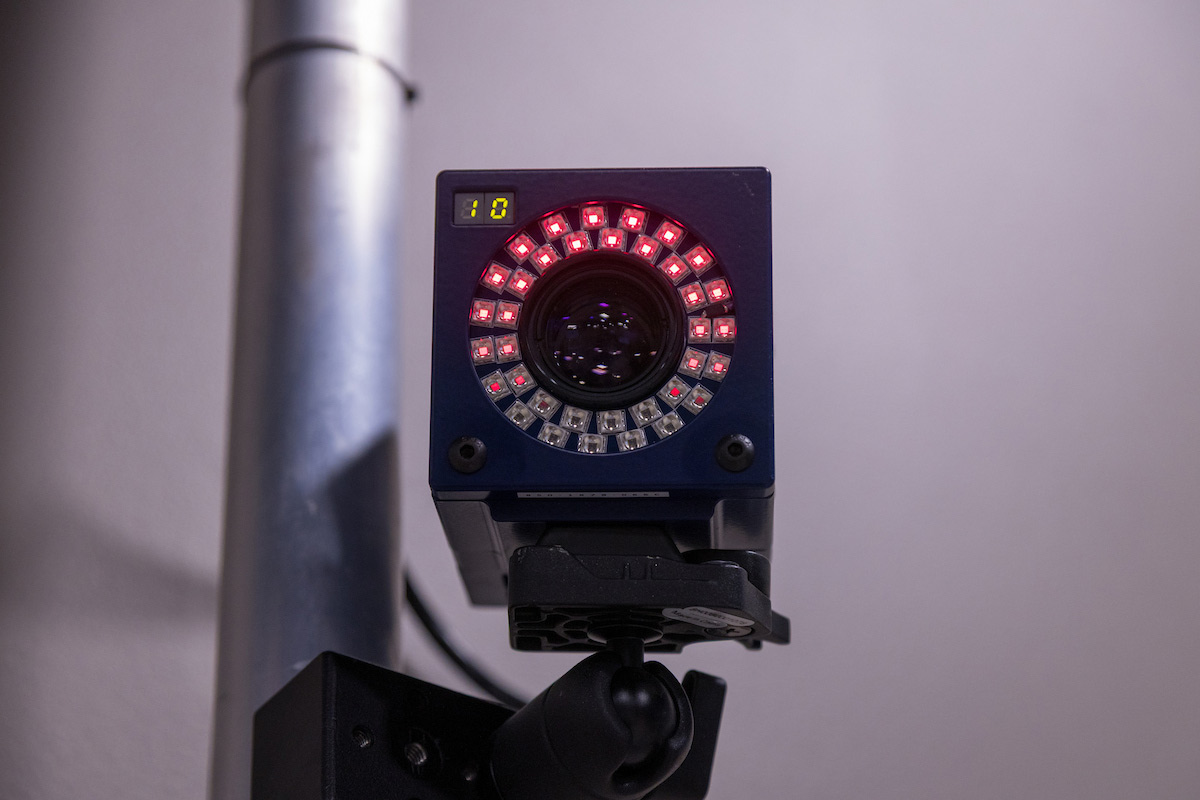

Lights hum. Cameras fixed to metal piping around the room blink to life. A low, rhythmic whir echoes from a treadmill. Researchers chatter while they check a complex system of motion capture sensors, computers, and monitors once, twice, and three times for good measure.

Today is a big day. Theo Brewer is about to arrive.

When he finally does, the air changes. He doesn’t knock. He bursts through, buzzing with energy and a familiar smile that quickly makes its way around the room.

Everything in the space is trained not just to study Theo’s movement, but to see his story.

This isn’t a clinic. There are no hospital gowns. It's a space designed for understanding human motion in a way that can transform a life like Theo’s.

Theo is like any other 9-year-old. He’s outgoing, loves riding his bike, listening to music, and swimming. Sometimes he’ll get up to a little mischief.

Except Theo does it all with cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and the kind of seizures that once stole his words.

In the Clinical Gait Analysis Lab, he’s not a patient. He’s a runner, a puzzle solver, a climber, a talker, a kid with a mission.

But it wasn’t always like this.

The Search for Answers

Theo’s early years were filled with questions. Born via emergency C-section at 35 weeks, he seemed to hit milestones like any other child.

But then between 15 to 18 months old, his speech began to regress and he developed a tip toe walk.

For the next several years, the Brewer family made repeated trips from their home in Wauneta, Nebraska – a village of less than 600 people northwest of McCook in southwest Nebraska – to Shriners Hospital in Minneapolis chasing a diagnosis that could explain what was happening.

Eventually, doctors identified cerebral palsy and epilepsy with myoclonic seizures.

Medications helped control the seizures, but Ashley Brewer – Theo’s mom, and Theo’s care team knew that wasn't the whole story.

But after nearly five years of traveling to Minneapolis once or twice a year for care, the burden became too much.

“It was just too expensive. We couldn’t continue,” Ashley said.

That’s when the search for deeper answers and more local support began.

She reached out to Children’s Nebraska in Omaha, hoping they could help transfer Theo’s care closer to home.

That call opened the door to a new care team and a new chapter.

Then two years into their care at Children’s Nebraska, Ashley and Theo were presented with a new opportunity.

One of Theo’s doctors mentioned the groundbreaking research at UNO’s Biomechanics program.

“She was like, ‘Hey, there’s this research at UNO that does gait studies. Would you want to be a part of that?’” Ashley says. “And I was like, absolutely. If it’s going to be able to further help him, there’s no question about not wanting to do it.”

That decision would lead to answers no previous provider had uncovered and ultimately, to a surgery that transformed Theo’s movement.

Changing Patient Care

For UNO Biomechanics assistant professor David Kingston, Ph.D., who directs the Movement Analysis Core Facility, every data point carries weight. Especially when it leads to answers for families like Theo’s.

The lab doesn’t just generate graphs and motion models. It provides critical information that surgeons can use to make life-changing decisions.

“We get to connect with families and for a few hours while we do world-class science in the background,” Kingston says. “But in reality, it’s so much more than that. By getting familiar with them on their day in the lab, we get to see the patient or the child in a more natural way…and that can truly change the care of patients.”

During Theo’s first gait study, Research Scientists Fabricio Magalhaes, Ph.D., and Felipe Yamaguchi, Ph.D., mapped his movement in extraordinary detail.

What happened next is the part of quiet revolution underway in the Clinical Gait Analysis Lab that is changing hundreds of lives like Theo’s.

It starts with motion capture sensors – those tiny, reflective dots you’ve seen in behind-the-scenes superhero movie clips and on video game character actors. Researchers attached them to Theo’s legs, back, arms, shoulders.

From that data, the team built a digital model of Theo’s walk.

Frame by frame, they discovered the muscles betraying him: hamstrings misfiring, nerve signals looping endlessly, wrong commands repeated with painful precision.

“They were able to pinpoint and locate that his hamstrings were what was causing his spastic diplegia,” Ashley says. “That is his form of cerebral palsy.”

From that, doctors could act.

Previous treatments like Botox injections offered only limited relief. But now, with accurate data and a clear diagnosis, Theo’s medical team at Children’s Nebraska had what they needed to recommend a more permanent solution: selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR), a nerve-targeting spinal surgery.

The lab’s data didn’t just support the choice. It gave Theo a shot.

Our Guy Theo

Now he climbs stairs without help. He rides a bike. He falls, gets up, and laughs.

Ask Ashley and she’ll tell you the biggest change isn’t physical. It’s in the way he fills a room.

“He’s freer,” she says. “He knows he can do things now. And when he walks in here, he knows people see more than his diagnosis.”

This is the thing about the gait lab.

It's technical. Hyper-precise. A marvel of academic engineering that outside of UNO’s campus can only be found at top medical research facilities. But it only works because its people lead with heart.

Kingston calls Theo “our guy.”

He talks about every child like he’s part of a big family, not a subject. And when he speaks about biomechanics, it sounds more like community stewardship than science. It’s about reducing the burden on families who shouldn't have to leave their community for answers.

“Often these families would have to travel out of state,” he explains. “The care that their child was receiving was impacted because of cost…It is truly an incredible opportunity as an academic to be able help these kiddos get a chance to become the people they can be.”

What used to require plane tickets and hotel stays is now a road trip for families like Ashley’s. And in a field that often feels clinical, the Omaha team makes it personal.

“We’re lucky,” Kingston said. “We get to do research that walks back into our lives. That makes a difference right now.”

Here for a Reason

Kingston hopes more families across Nebraska will reach out. He knows that children with cerebral palsy, and other movement disorders, exist across a wide spectrum and not all of them are currently being referred for motion analysis.

“Parents, please reach out,” he said. “Do not be a stranger. UNO Biomechanics is happy to be a home for you.”

The lab has already worked with more than 200 pediatric patients like Theo, and thanks to partnerships with institutions like Children’s, they’re just getting started.

Would Ashley recommend more families like hers to Kingston and the Clinical Gait Analysis Lab?

Yes, without hesitation.

“Just because your child has a disability doesn’t mean that they’re broken,” she said. “They are here for a reason. Make sure you get the help and the team is on your side, because without that, what are you going to do?”

A New Test

There’s a new test today.

It’s a year-and-a-half post-SDR surgery and Theo is back to check his progress.

“If it wasn’t for the gait study and the amazing team at Children’s Hospital,” Ashley said. “We probably wouldn’t be as far as we are today.”

Theo patiently waits as the team checks his sensors. He hums. Taps his foot. Stretches a little. Then, on cue, he walks. Confident, steady, focused.

He’s their guy.

“He doesn’t let anything slow him down,” Ashley says, glancing at Theo. “He sees a problem and he’s going to try and figure it out hell or high water.”

Each step he takes is data. And proof.

Not just that the lab works. That it matters.

About the University of Nebraska at Omaha

Located in one of America’s best cities to live, work and learn, the University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO) is Nebraska’s premier metropolitan university. With more than 15,000 students enrolled in 200-plus programs of study, UNO is recognized nationally for its online education, graduate education, military friendliness and community engagement efforts. Founded in 1908, UNO has served learners of all backgrounds for more than 100 years and is dedicated to another century of excellence both in the classroom and in the community.

Follow UNO on Facebook, Twitter (X), Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube.