Distance Learning Module 8 - Floods and Natural Hazard Management

DEALING WITH WATER-RELATED NATURAL HAZARDS

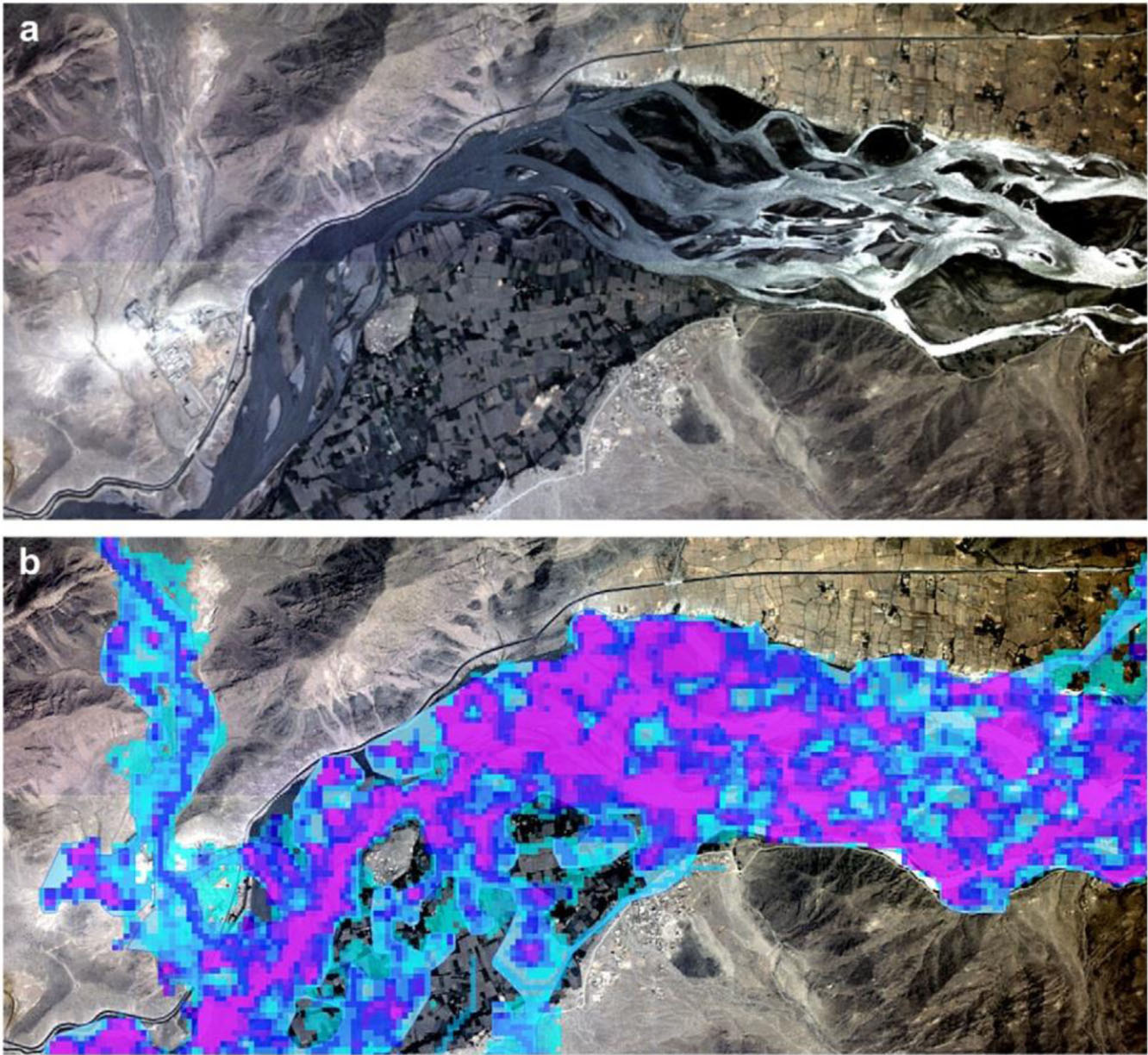

• Too much water in a short time produces floods (Figure 8.1A&B) – too little water produces droughts Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.1A. Flooding on the Helmand River (USAID).

Figure 8.1A. Flooding on the Helmand River (USAID).

Figure 8.1B. Heavy rains in Kabul, 2 April 2014 (Voice of America News).

Figure 8.2. Drought conditions in Afghanistan in 2006 (After UNHCR and Albawaba).

Figure 8.2. Drought conditions in Afghanistan in 2006 (After UNHCR and Albawaba).• Floods come from rapid snow-melt, and rain storms from the monsoon from Pakistan, or from Westerly Winds all the way from the Mediterranean and Atlantic Ocean.

• Some water floods can be predicted statistically or by computer analysis, especially if good large-scale topographic maps are available.

• Computer cellular automata and high resolution digital topographic data for the whole of Afghanistan were used by scientists from the University of Nebraska at Omaha and from NATO (ISAF) to produce detailed flood hazard maps for the whole of Afghanistan (Figures 8.3 & 8.4).

Figure 8.3. Orthophotograph image (a); of lower Kunar River showing the AFG-FHM cellular overlay with about an 8.7 m flood depth (b). These flood maps were made for all of Afghanistan to see where certain depths of waters would go, and what they would cover when the water was raised higher and higher by computer. This work was done on very high resolution kinds of maps that were only available to ISAF to work with but attempts are being made to have this methodology be released to the Afghan government.

Figure 8.3. Orthophotograph image (a); of lower Kunar River showing the AFG-FHM cellular overlay with about an 8.7 m flood depth (b). These flood maps were made for all of Afghanistan to see where certain depths of waters would go, and what they would cover when the water was raised higher and higher by computer. This work was done on very high resolution kinds of maps that were only available to ISAF to work with but attempts are being made to have this methodology be released to the Afghan government.

Figure 8.4. Flood hazard map of Afghanistan derived from the Afghanistan flood hazard map (AFG-FHM) of Hagen et al. (2010) The map on line is capable of considerable enlargement, although the original could generally be accurately enlarged to 1:100,000. Red indicates high flood hazard and dark blue is moderate flood hazard.

• Droughts come in several different types that add together and cause major problems (Figure 8.5 & 8.6).

Figure 8.5. Graphic of interrelationships between initial meteorological drought, followed by the cascade of successive agricultural, hydrological, and socio-economic and political forms of drought (After National Drought Mitigation Center, University of Nebraska – Lincoln, USA, in WMO, 2006).

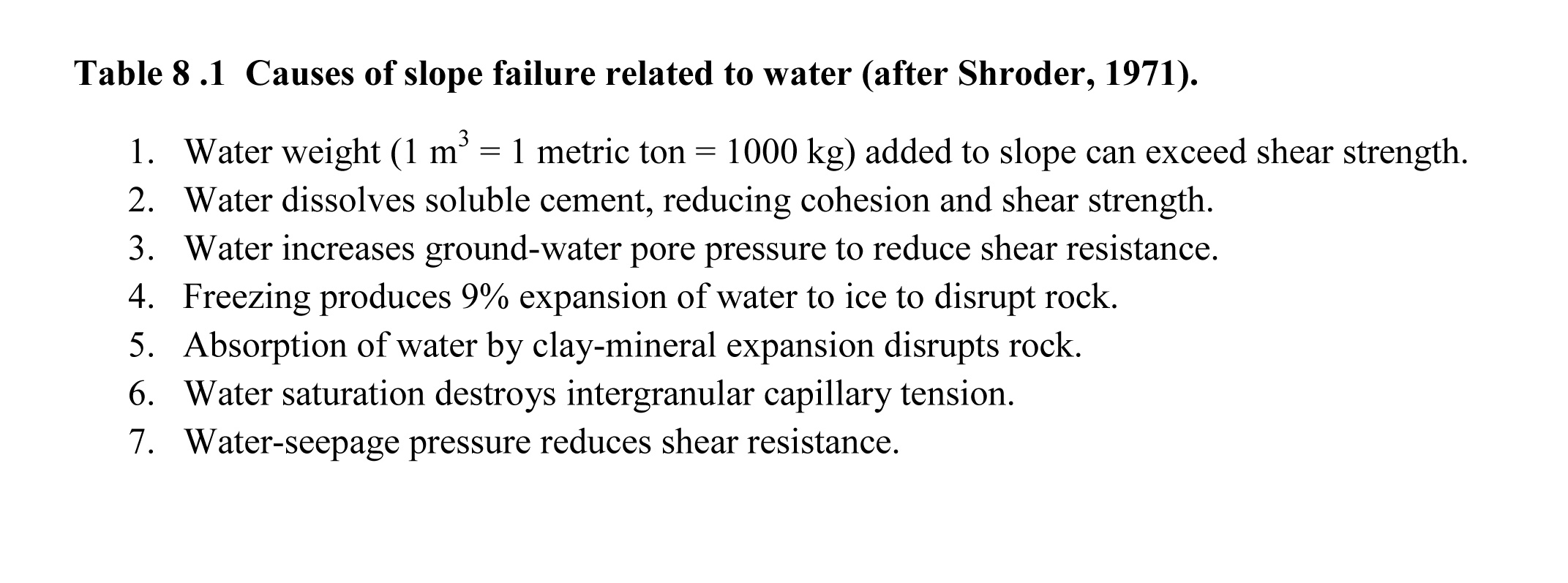

• Water causes landslides for many different reasons (Table 8.1).

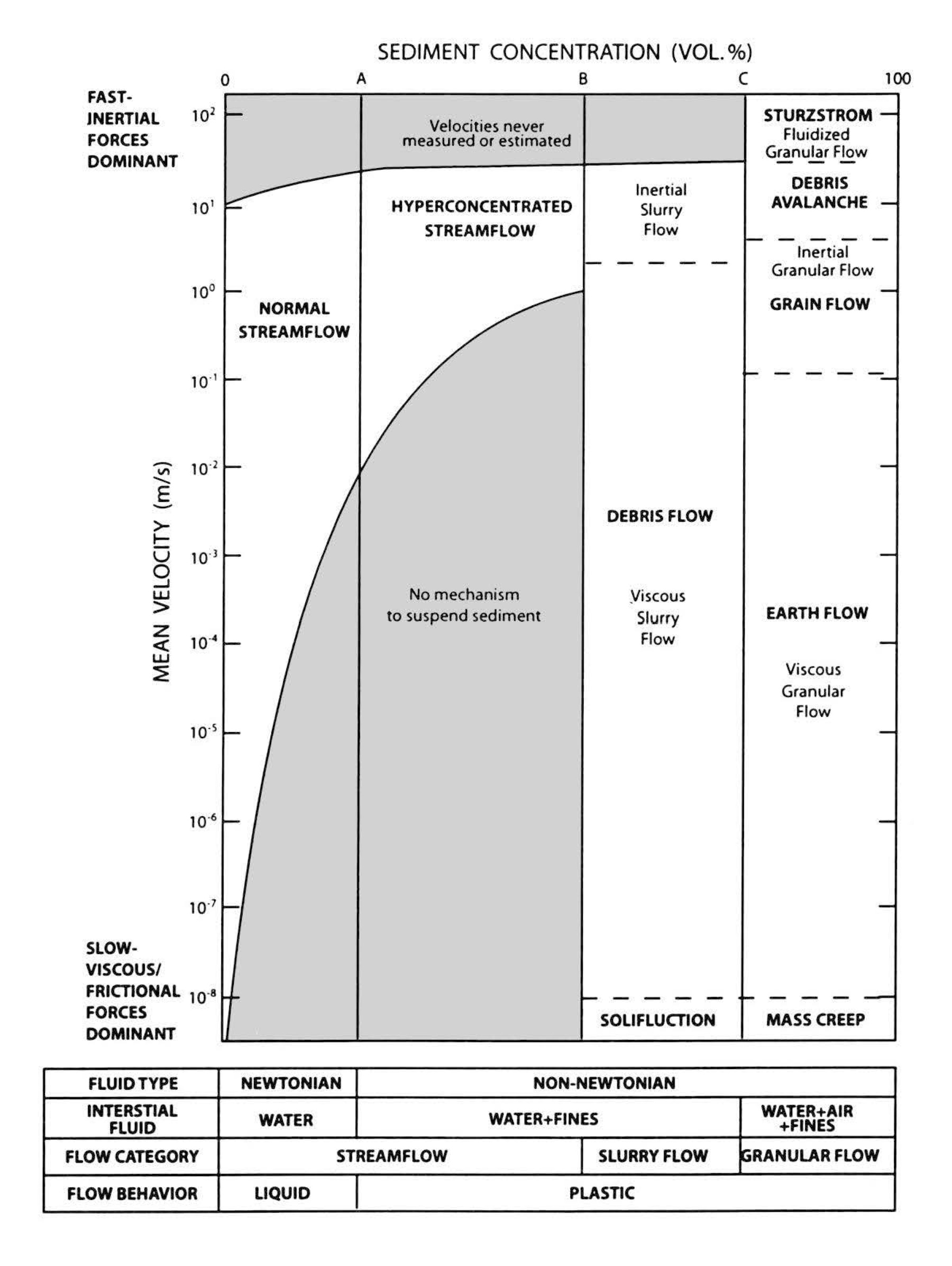

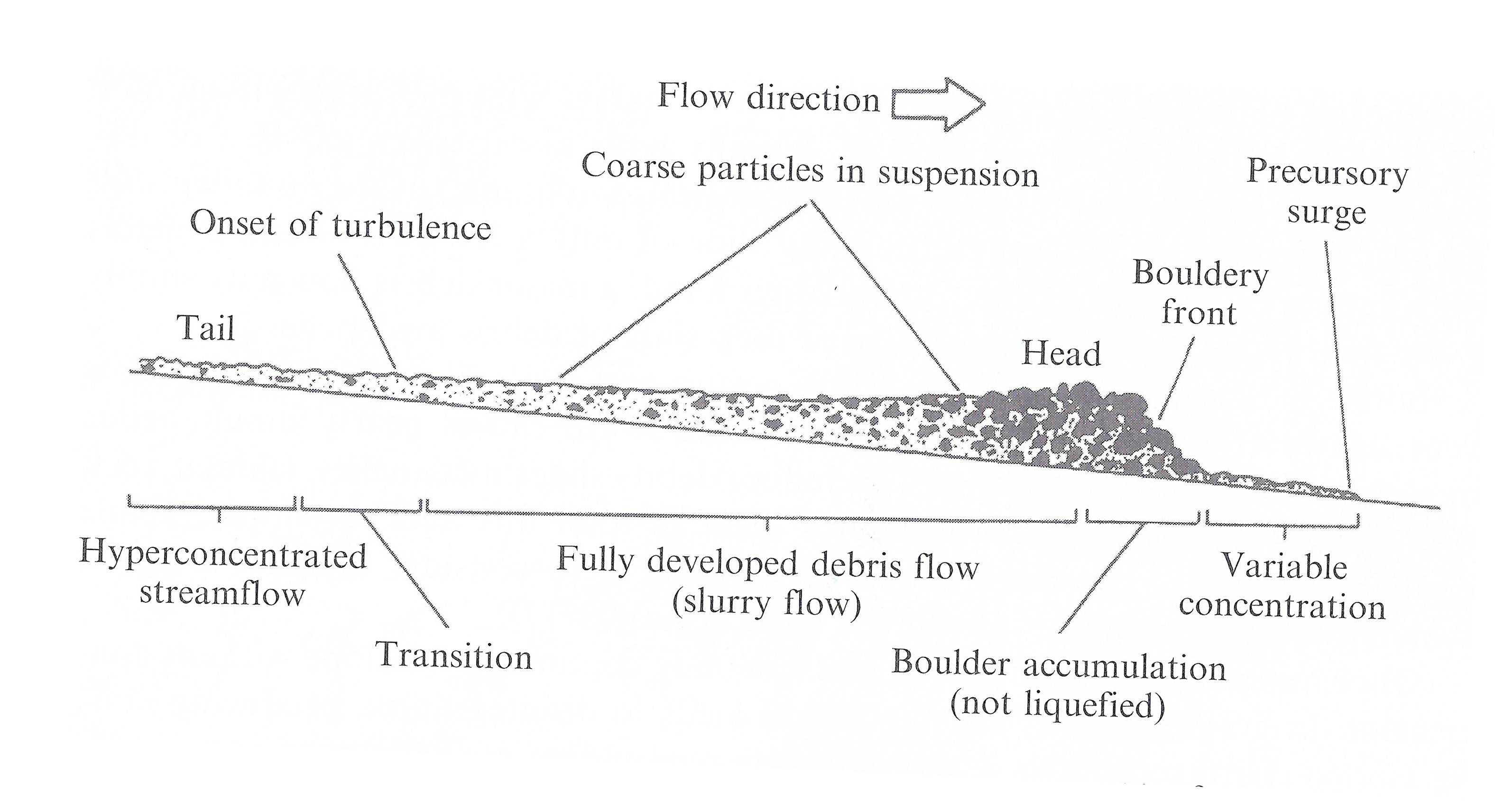

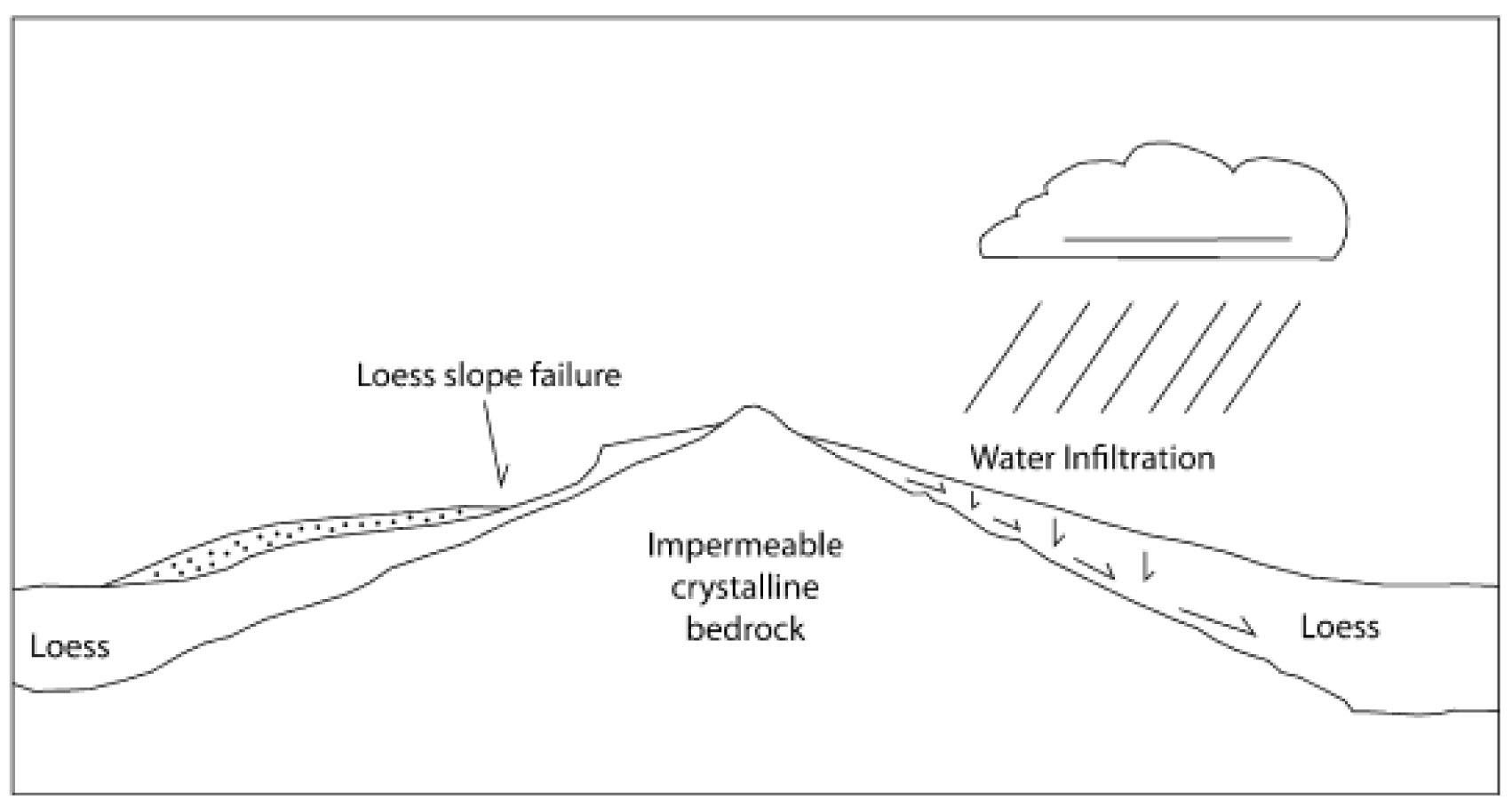

• Water is very heavy and when added in large quantities to mountain slopes it can run off in concentrated wet masses of mud and rocks (rapid wet debris flows; Figures 8.7 & 8.8), or it can cause widespread areas of hillslopes to collapse under the increased weight into different kinds of landslides (loess flow, hillside slump; Figures 8.9 & 8.10), or it can come down as snow, which slides off in huge masses called snow avalanches (Figure 8.11) .

Figure 8.7. Diagram of various sediment concentrations mixed with water plotted against mean velocity showing the range of debris flows (after Pierson and Costa, 1987, and Shroder 2014). A continuum exists of different kinds of hazardous mixtures of sediment particles and water, depending upon the percentages of sediment and water.

Figure 8.7. Diagram of various sediment concentrations mixed with water plotted against mean velocity showing the range of debris flows (after Pierson and Costa, 1987, and Shroder 2014). A continuum exists of different kinds of hazardous mixtures of sediment particles and water, depending upon the percentages of sediment and water.

Figure 8.8. Diagram of a debris-flow surge with a boulder front (after Hungr, 2005). These mixtures of sediment particles and water move at different speeds as they flow down mountain valleys.

Figure 8.8. Diagram of a debris-flow surge with a boulder front (after Hungr, 2005). These mixtures of sediment particles and water move at different speeds as they flow down mountain valleys.

Figure 8.9. Cross section of loess-sediment blanketed over crystalline bedrock, which is very similar to the situation of the Ak Barak loess-flow where the crystalline bedrock is exposed at the bottom of the loess hill where the village was located. The high loess hill on the other side had been showing with cracks and wrinkle ridges that it was ready to fail and come down to cover the village but no one noticed that this would happen (after Shroder et al., 2011b; Shroder, 2014).

Figure 8.9. Cross section of loess-sediment blanketed over crystalline bedrock, which is very similar to the situation of the Ak Barak loess-flow where the crystalline bedrock is exposed at the bottom of the loess hill where the village was located. The high loess hill on the other side had been showing with cracks and wrinkle ridges that it was ready to fail and come down to cover the village but no one noticed that this would happen (after Shroder et al., 2011b; Shroder, 2014).

Figure 8.10. Low-altitude oblique aerial photograph of Ab Barak loess flow in southern Badakhshan Province that occurred on 2 May 2014; view to south to southwest. The village in the front below is built of hard crystalline bedrock that is gray. Across to the other side, the silty loess is composed of wind-blown silt deposits known as loess. The main slope failure of loess has moved to the east, upstream, as well as to the west downstream, in two successive but different directions of movement, with the east (upstream to the left) motion being first, and the west (downstream to the right) being second. A marked basin of ‘profound concavity’ (Shroder, 1976) occurs on the upper right of the hilltop that marks a basin or earlier strong erosion that was probably also a loess flow (after Wakhil Kohsar/Getty Images; On line by The Atlantic; Ask for permission).

Figure 8.10. Low-altitude oblique aerial photograph of Ab Barak loess flow in southern Badakhshan Province that occurred on 2 May 2014; view to south to southwest. The village in the front below is built of hard crystalline bedrock that is gray. Across to the other side, the silty loess is composed of wind-blown silt deposits known as loess. The main slope failure of loess has moved to the east, upstream, as well as to the west downstream, in two successive but different directions of movement, with the east (upstream to the left) motion being first, and the west (downstream to the right) being second. A marked basin of ‘profound concavity’ (Shroder, 1976) occurs on the upper right of the hilltop that marks a basin or earlier strong erosion that was probably also a loess flow (after Wakhil Kohsar/Getty Images; On line by The Atlantic; Ask for permission).

Figure 8.11. Snow avalanche at Salang Pass in 2010 showing wrecked cars downhill from snow sheds built by Soviet engineers to protect against avalanches; clearly the sheds were not built long enough, or did not cover enough of the road to protect against these serious hazards.

Figure 8.11. Snow avalanche at Salang Pass in 2010 showing wrecked cars downhill from snow sheds built by Soviet engineers to protect against avalanches; clearly the sheds were not built long enough, or did not cover enough of the road to protect against these serious hazards.

• Forewarnings or prediction of some landslides are possible by professional scientists who have experience (Figure 8.12).

Figure 8.12. Pre-failure scene from Google Earth™ showing approximately the same view direction as Figure 8.10, but the scene was acquired prior to the loess-flow failure. A number of what appear to be incipient ground cracks, turf rolls or wrinkle ridges, and eroded gullies occur in the middle of the slope and give an indication of coming slope-failure problems, as well as evidence that the hazard was looming in the future, and could have been predicted as a possible hazard zone, had anyone had appropriate knowledge and experience. Landslide experts can predict this kind of serious hazard, and this should be done in future for many places in Afghanistan.

Figure 8.12. Pre-failure scene from Google Earth™ showing approximately the same view direction as Figure 8.10, but the scene was acquired prior to the loess-flow failure. A number of what appear to be incipient ground cracks, turf rolls or wrinkle ridges, and eroded gullies occur in the middle of the slope and give an indication of coming slope-failure problems, as well as evidence that the hazard was looming in the future, and could have been predicted as a possible hazard zone, had anyone had appropriate knowledge and experience. Landslide experts can predict this kind of serious hazard, and this should be done in future for many places in Afghanistan.

• Extensive unstable, landslide areas of Afghanistan have been mapped for hazardous areas of the country by personnel from the University of Nebraska at Omaha (Figure 8.13).

Figure 8.13. Vertical-downward view of Kuchnay Makhay slope-failure complex that crosses the Chaman Fault zone. The red bar in the upper left is 1 km in length. North is up. This landslide appears to be the result of a torrential rainstorm, but it is possible that a strong earthquake shock also could have produced the landslide on the Chaman – Quetta fault that passes through here on its way to Kabul and on north to the Panshir Valley and Badakhshan.

Figure 8.13. Vertical-downward view of Kuchnay Makhay slope-failure complex that crosses the Chaman Fault zone. The red bar in the upper left is 1 km in length. North is up. This landslide appears to be the result of a torrential rainstorm, but it is possible that a strong earthquake shock also could have produced the landslide on the Chaman – Quetta fault that passes through here on its way to Kabul and on north to the Panshir Valley and Badakhshan.

REFERENCES

Shroder, J.F., Jr., 1989. Slope failure: extent and economic significance in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In: Landslides: extent and economic significance in the world. eds. E.E. Brabb and B.L. Harrod, A.A. Balkema, Rotterdam, Netherlands, p. 325-341.

Shroder, J.F.,Jr. B.J. Weihs, 2010. Geomorphology of the Lake Shewa landslide dam, Badakshan, Afghanistan, using remote sensing data. Geografiska Annaler 92A (4): 471-486.

Shroder, J.F., Jr., B. Weihs, and M. Schettler, 2011. Mass movement in northeast Afghanistan. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of the Earth; 36:1267-1286; doi:10.1016/j.pce.2011.03.003

Shroder, J.F., Schettler, M.J., Weihs, B.J., 2011. Loess failure in northeast Afghanistan. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, 36:1287-1293;doi:10.1016/j.pce.2011.03.001