Distance Learning Module 15 - Afghanistan Ground Water Issues

Water underground occurs in areas dominated by sediments (mud, clay, silt, sand, gravel) and sedimentary rocks (shale, sandstone, conglomerate, limestone).

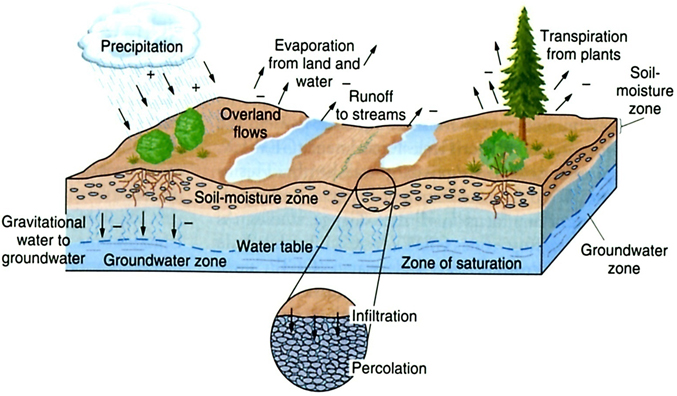

Figure 16.1. Picture of unconfined, water-table water underground showing different zones: uppermost soil moisture where precipitation infiltrates downward to the water table where all the open pore spaces are filled or saturated.

Figure 16.1. Picture of unconfined, water-table water underground showing different zones: uppermost soil moisture where precipitation infiltrates downward to the water table where all the open pore spaces are filled or saturated. Figure 16.2. Picture of unconfined, water-table water underground with the uppermost Zone of Aeration and the lowermost Zone of Saturation below the Water Table.

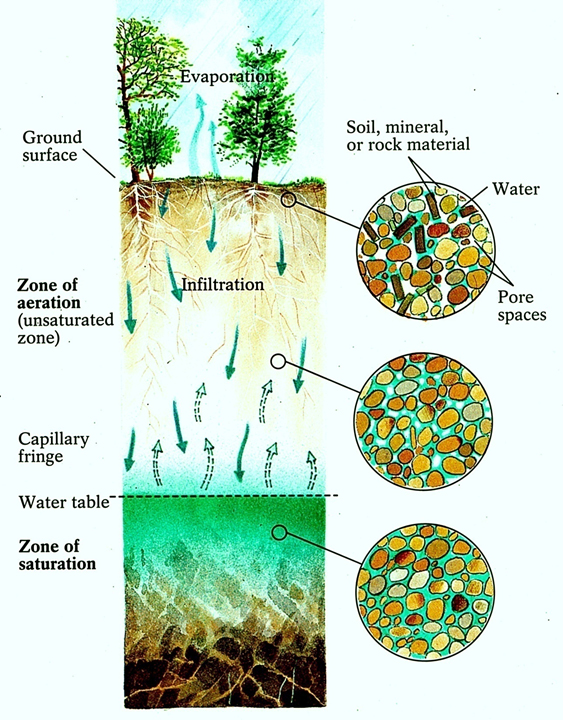

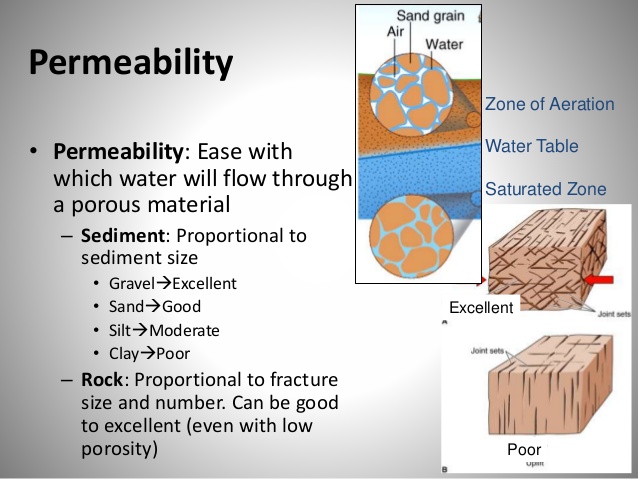

Figure 16.2. Picture of unconfined, water-table water underground with the uppermost Zone of Aeration and the lowermost Zone of Saturation below the Water Table.Water occurs in small open spaces in such rocks called ‘pores’, or are ‘porosity’.

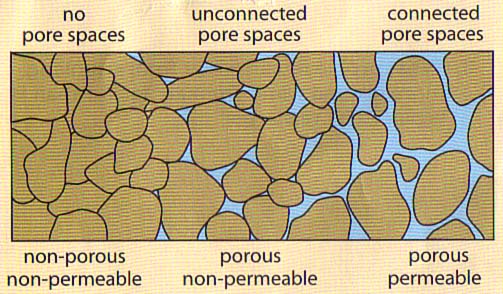

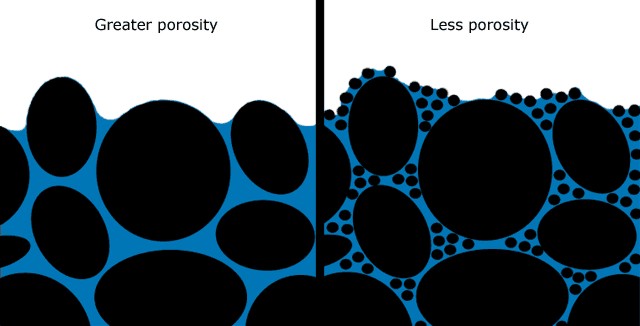

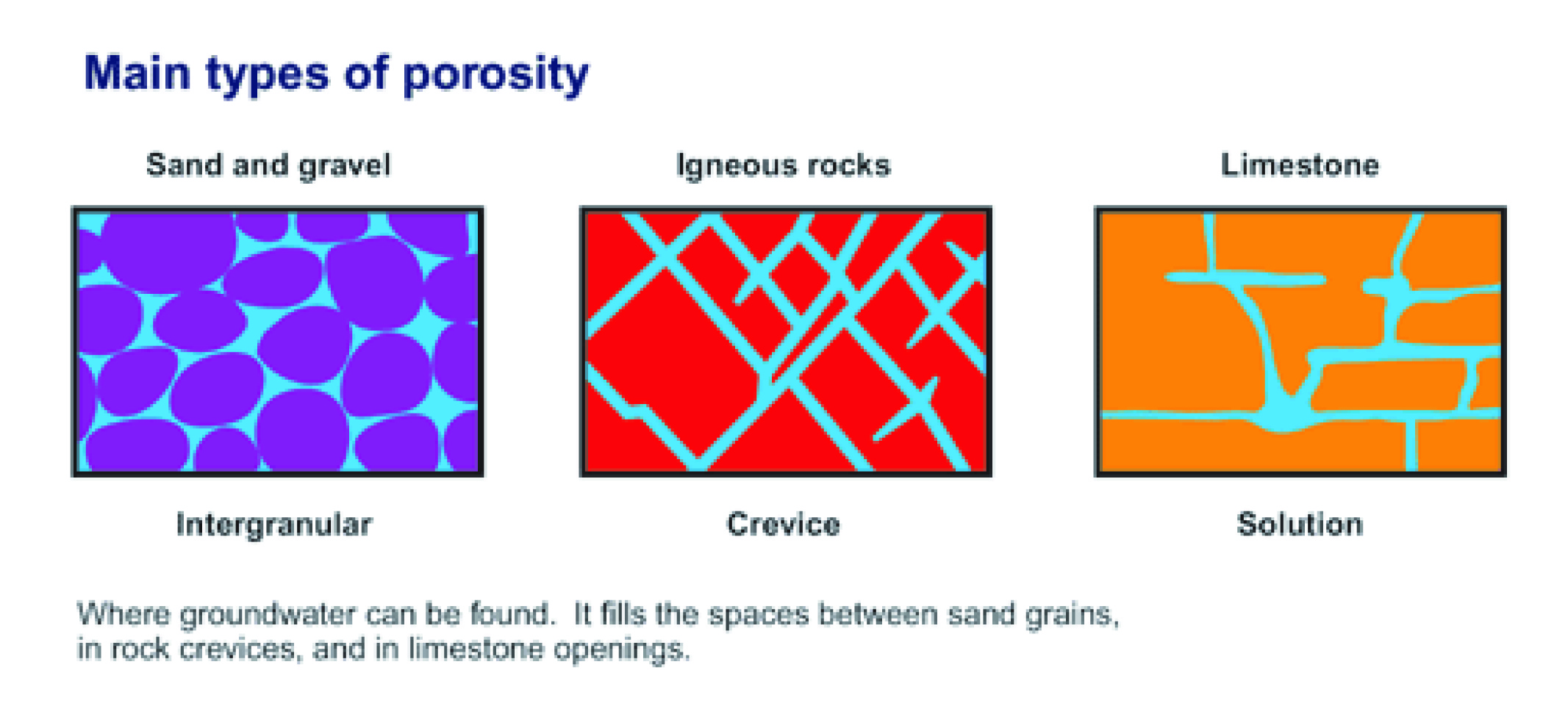

Figure 16.3A,B,C &D. Porosity is the open spaces underground where water can collect and permeability is the amount of connection between the pore spaces. The best ground-water aquifers are sands and gravels, because they have the most interconnected pore spaces.

Figure 16.3A,B,C &D. Porosity is the open spaces underground where water can collect and permeability is the amount of connection between the pore spaces. The best ground-water aquifers are sands and gravels, because they have the most interconnected pore spaces.

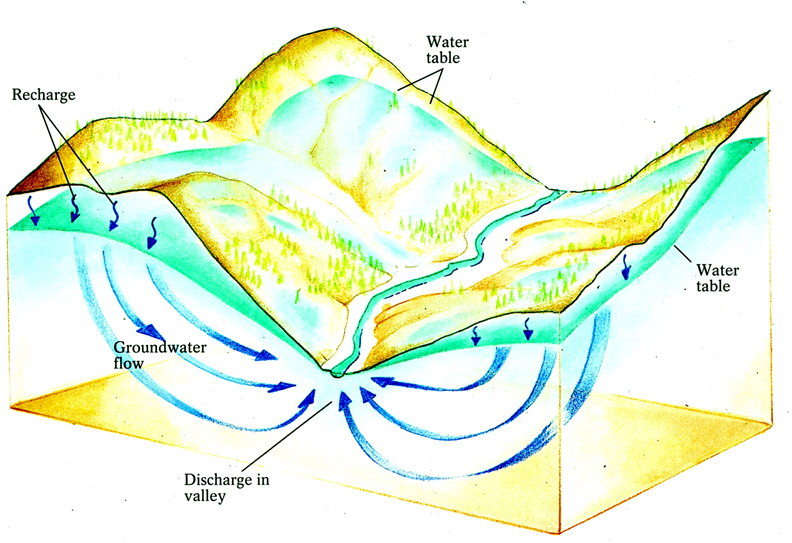

Figure 16.4. Underground water flow through the connected pore spaces.

Figure 16.4. Underground water flow through the connected pore spaces.

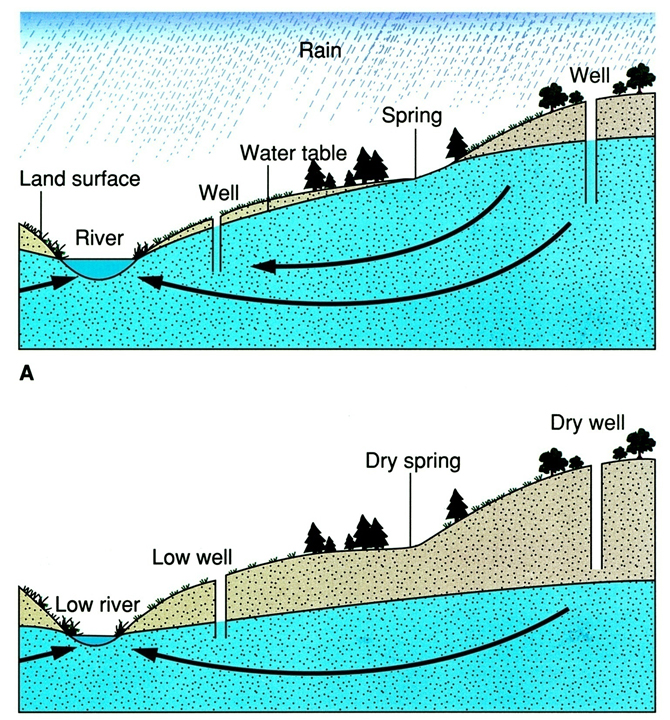

Figure 16.5. Two pictures of underground water table fluctuation up and down between (A) the wet season and (B) the dry season. The more shallow wells can dry up in the dry season when the water table goes down.

Figure 16.5. Two pictures of underground water table fluctuation up and down between (A) the wet season and (B) the dry season. The more shallow wells can dry up in the dry season when the water table goes down.

If the pore spaces in the rocks are connected so that the water can move underground, that is called permeability.

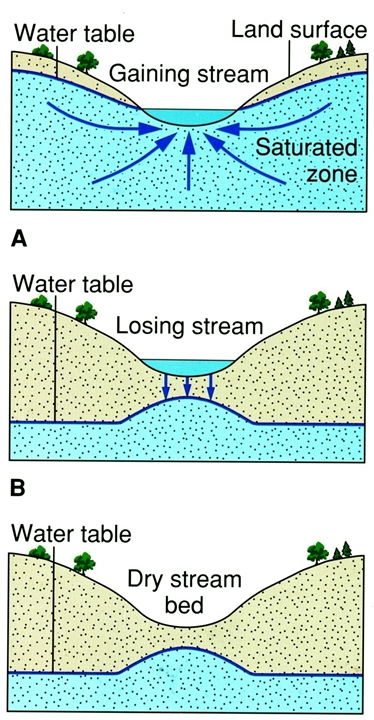

Figure 16.6. Three pictures of gaining streams that receive ground-water base flow (uppermost picture), (A) losing stream where water flows into the ground from the river, and (B) dry stream bed that may have a raised water table under it from where previous rain water drained down into it.

Figure 16.6. Three pictures of gaining streams that receive ground-water base flow (uppermost picture), (A) losing stream where water flows into the ground from the river, and (B) dry stream bed that may have a raised water table under it from where previous rain water drained down into it.

The highest porosity sediments and rocks are muds and shales, but they have very low permeability and will give no water.

The highest porosity and permeability sediments and sedimentary rocks are sands and gravels, or sandstones. These form water-filled aquifers, which can give good water.

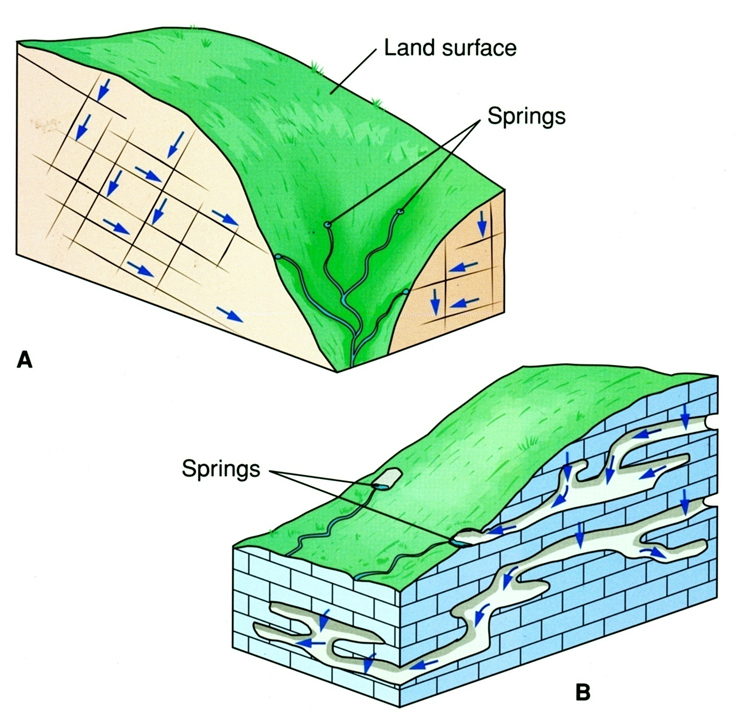

Hard crystalline rocks such as granite in the mountains may only have water trapped in cracks and fissures, which are called ‘joints’.

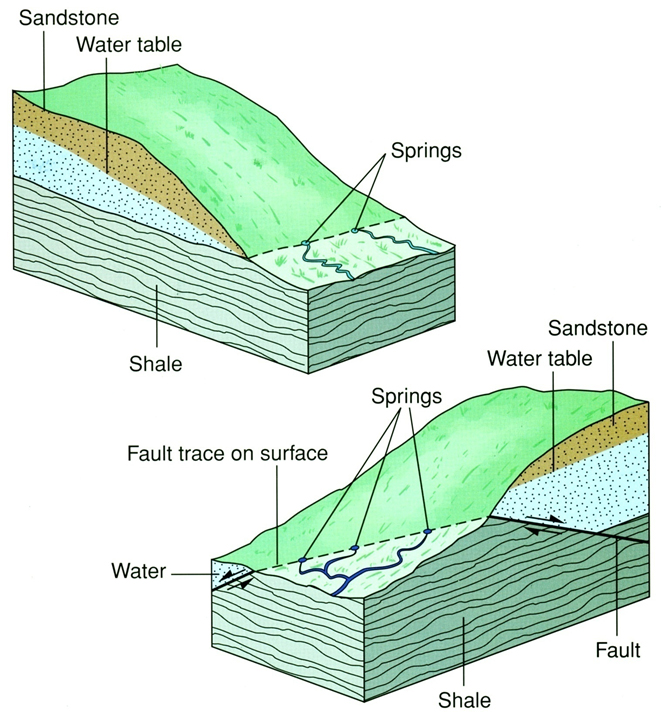

Figure 16.7. Unconfined, water-table water situations and water springs in (upper) sandstone and shale, and (lower) faulted (broken) sedimentary rocks.

Figure 16.7. Unconfined, water-table water situations and water springs in (upper) sandstone and shale, and (lower) faulted (broken) sedimentary rocks.

Figure 16.8. Unconfined, water-table water situations and water springs in (A) fractured crystalline rock such as granite, and (B) limestone caves.

Figure 16.8. Unconfined, water-table water situations and water springs in (A) fractured crystalline rock such as granite, and (B) limestone caves.

Underground water is dominated by what is called unconfined (no pressure) or water- table water in aquifers, which can be located by digging or drilling down into the earth where the water fills in between soil particles.

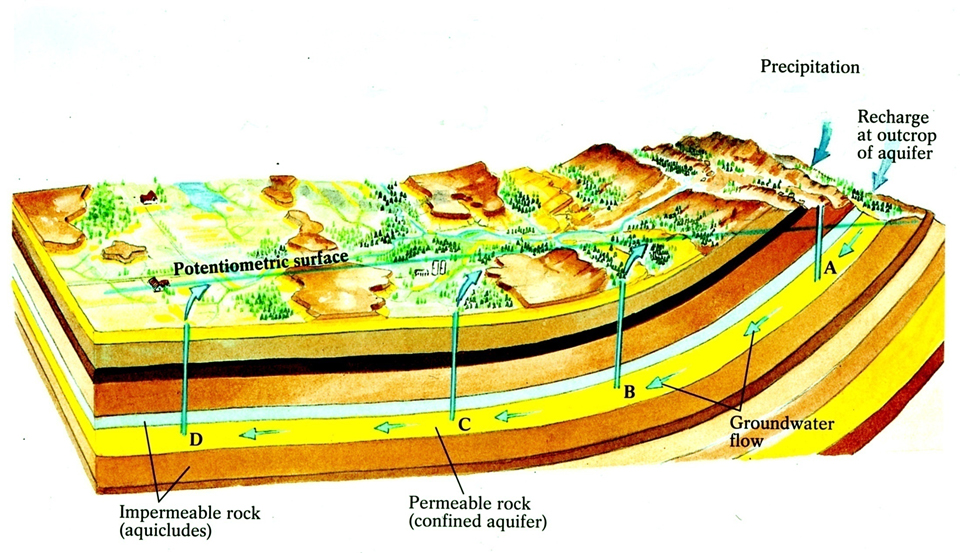

Figure 16.9. Confined, artesian water where the recharge zone is in the mountains on the right, and the ground water percolates downward to come into wells A, B, C, and D. The water will rise in the wells toward the potentiometric surface and may flow out on the ground.

Figure 16.9. Confined, artesian water where the recharge zone is in the mountains on the right, and the ground water percolates downward to come into wells A, B, C, and D. The water will rise in the wells toward the potentiometric surface and may flow out on the ground.

Underground water that is under pressure to rise up in the well to perhaps flow out on the ground is artesian water, and its source or recharge area is generally some distance away in the mountains.

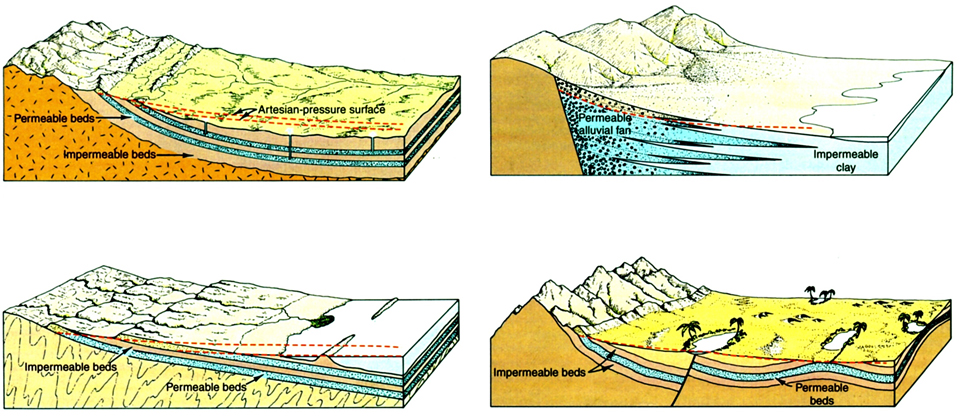

Figure 16.10. Four situations deep underground in Afghanistan that can produce artesian water.

Figure 16.10. Four situations deep underground in Afghanistan that can produce artesian water.

Traditional karez in Afghanistan tap into water-table water, and because these irrigation systems only tap into the upper part of the water table, they do not remove as much water from the underground.

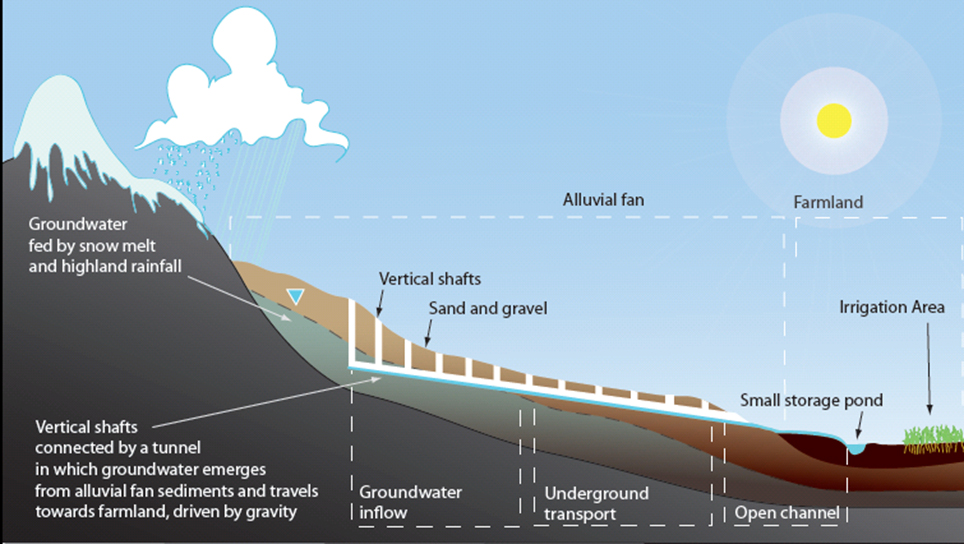

Figure 16.11. Drawing of karez irrigation that uses only the upper parts of the unconfined, water table water where the long underground tunnel intersects the water table and carries it out to the surface for people’s use.

Figure 16.11. Drawing of karez irrigation that uses only the upper parts of the unconfined, water table water where the long underground tunnel intersects the water table and carries it out to the surface for people’s use.

Figure 16.12. Photograph of karez openings on the surface, some of which are closed and filled in where the tunnel underground has collapsed and a mew tunnel had to be dug beside it.

Figure 16.12. Photograph of karez openings on the surface, some of which are closed and filled in where the tunnel underground has collapsed and a mew tunnel had to be dug beside it.

Over-pumping of underground water by electric and diesel pumps can pull down the water table and cause many karez to dry up.

Climate change (droughts) also cause the water table to decline and result in wells that dry up.

Most underground water comes from rain and snowmelt, which is generally pure fresh water, but if much salt is blown in by the wind, or if contamination is produced by people around wells or other pollution sources such as latrines of human or animal waste, then the water is spoiled.

Figure 16.13. Kabul River during low water showing how dirt and garbage is thrown into it to cause polluted water. Such dirty water is a major source of disease and the contaminated water can infiltrate down through the riverbed to the underground and pollute the ground water too.

Figure 16.14. Children in Kabul selling vegetables over an open sewer ditch (juie) where the contaminated water is poured on the vegetables, which spreads disease.

Figure 16.14. Children in Kabul selling vegetables over an open sewer ditch (juie) where the contaminated water is poured on the vegetables, which spreads disease.

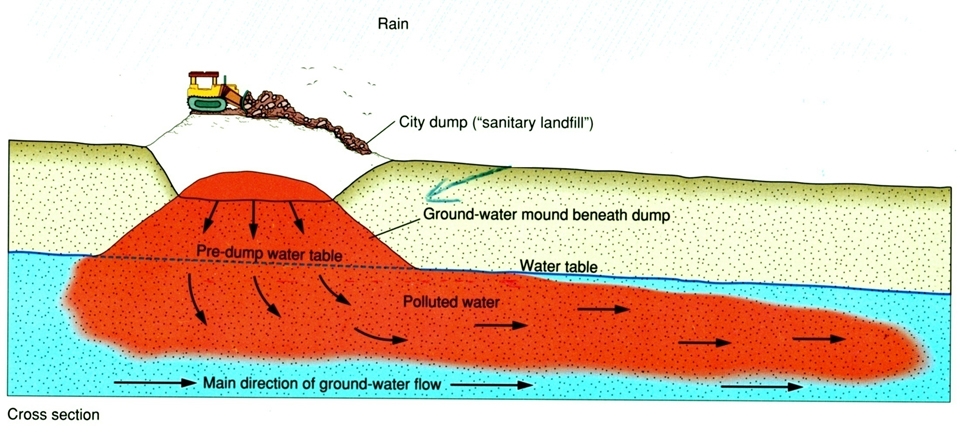

Figure 16.15. Drawing of how garbage from the city contaminates the unconfined, water-table water.

Figure 16.15. Drawing of how garbage from the city contaminates the unconfined, water-table water.

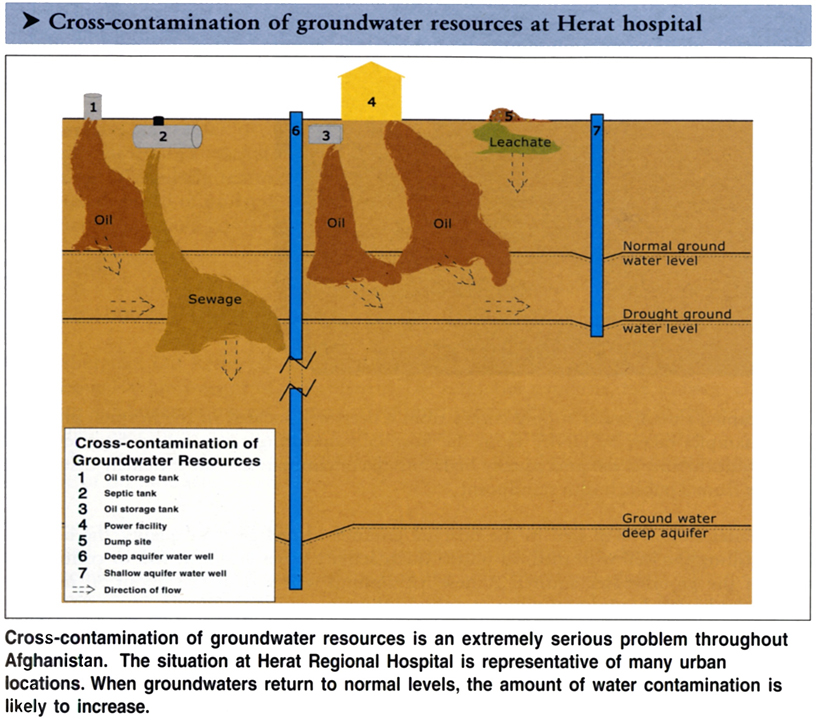

Figure 16.16. Cross section underground in Herat to show different types of ground-water pollution.

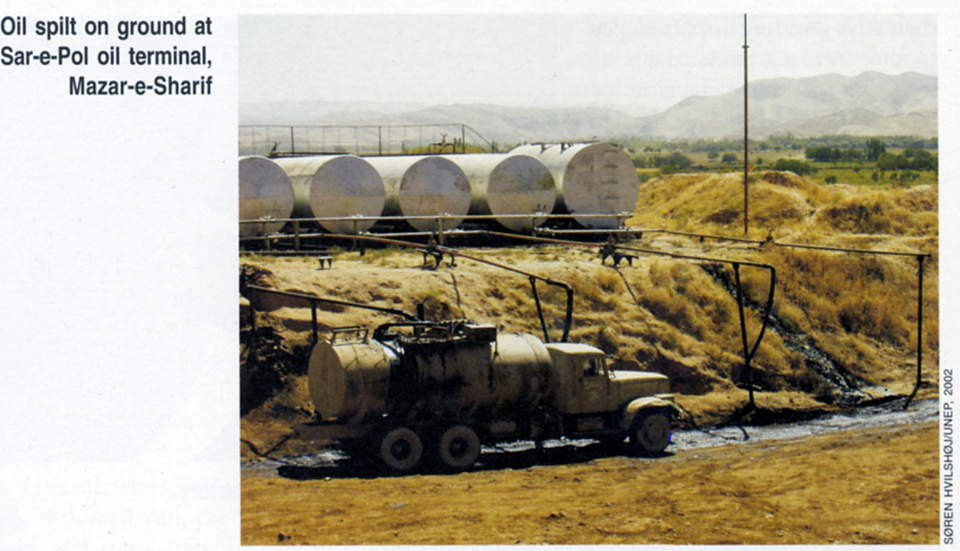

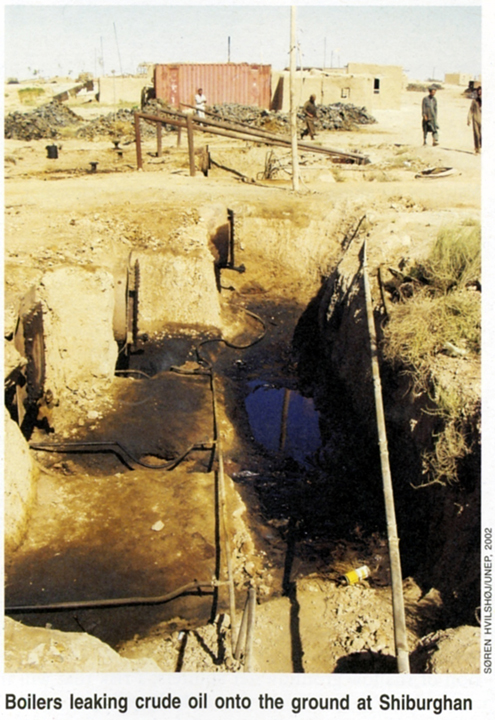

Figure 16.17. Oil in Shiberghan spills on the surface but goes down to contaminate the water table.

Figure 16.18. Oil-contaminated ground water in Shiberghan.

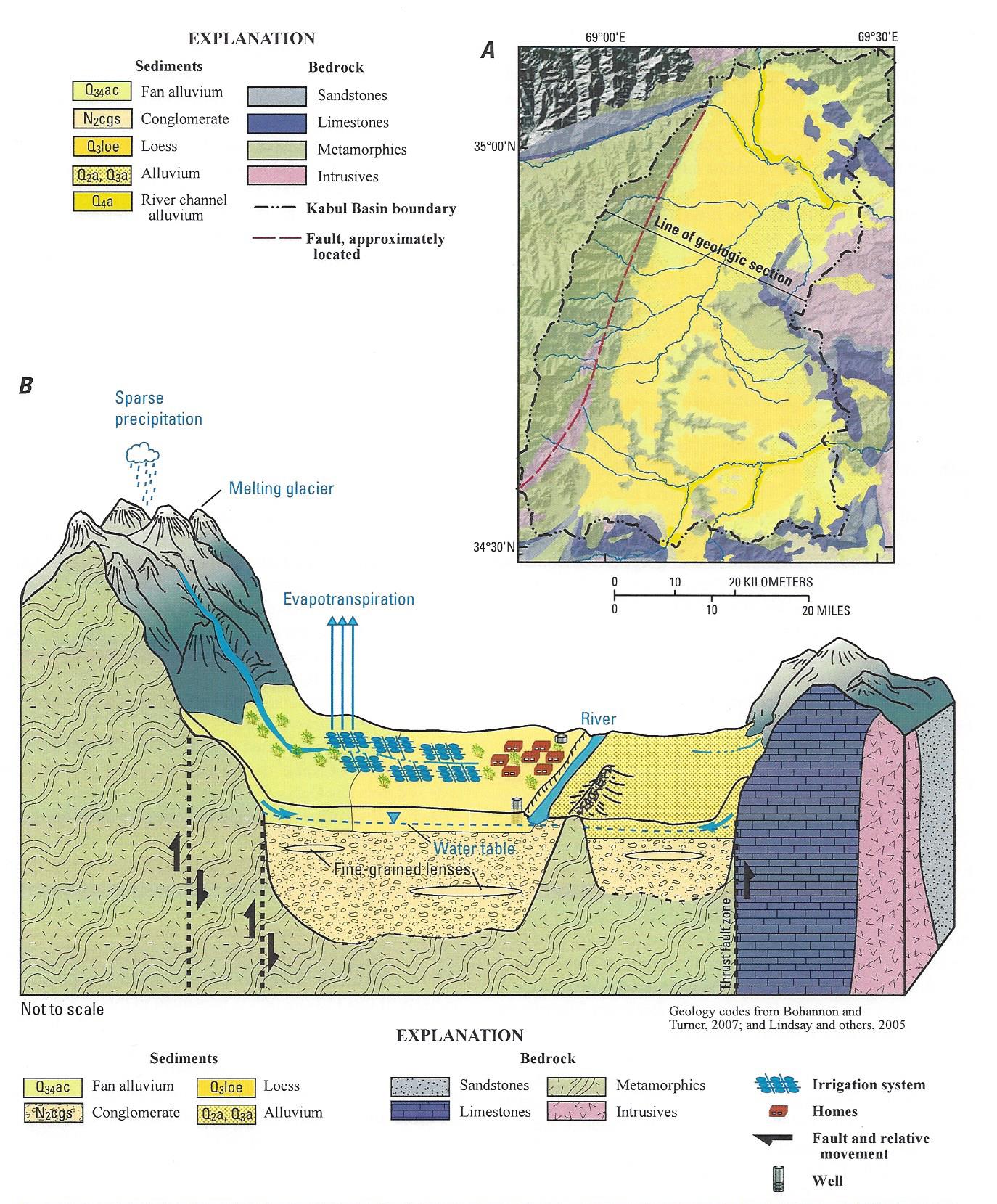

In Afghanistan the largest sedimentary basins (Kabul Basin, Jalalabad Basin, Seistan Basin, Bamiyan Basin, Herat Basin, etc.) are filled with sands and gravels that contain much underground water.

In the Hindu Kush mountains of Afghanistan, the crystalline rocks of igneous granite and metamorphic gneiss and other rocks only hold water in cracks and fissures in the rock, which can only be obtained by expensive drilling of the bedrock. Small amounts of water can be obtained in such areas by digging wells in the flatter floodplain areas of rivers in mountain valleys.

If underground water is pumped out in large amounts without replacement in dry areas, this is considered to be ‘mining’ the ground water and it will pull down the water table by forming what is called a ‘cone of depression’ of the surface of the water table underground.

Recharge of ground water is done in many dry areas in the world by forcing floodwaters to flow out into artificially dug recharge basins so that the water can soak into the ground and raise the water table.

In some border areas of Afghanistan, over-pumping of groundwater outside of Afghanistan pulls down the water table, which causes underground water in Afghanistan to flow away from Afghanistan and into the other country.

Figure 16.19. Drawing of the ground-water basin of Kabul.

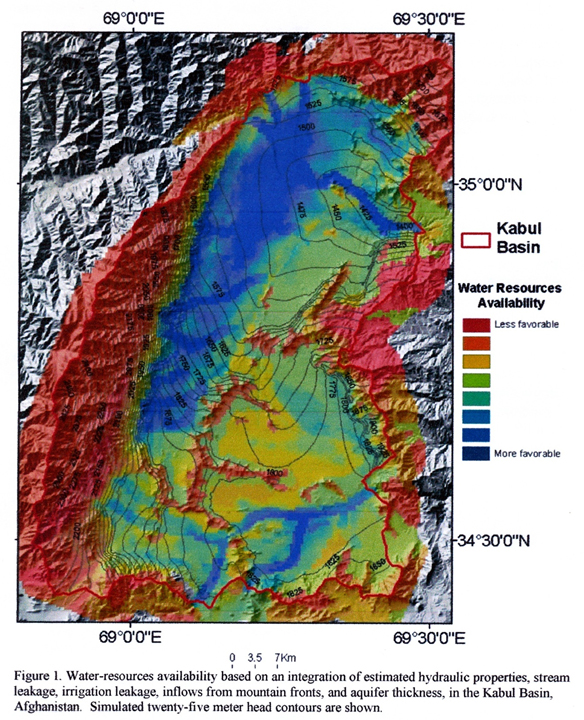

Figure 16.20. Map of water resources in the Kabul Basin. The ground water directly under Kabul City (south and browner part of the map) has been drawn down, and much of it is contaminated. North of Kabul, the water underground is much higher and more fresh.